Hopf fibration

In the mathematical field of topology, the Hopf fibration (also known as the Hopf bundle or Hopf map) describes a 3-sphere (a hypersphere in four-dimensional space) in terms of circles and an ordinary sphere. Discovered by Heinz Hopf in 1931, it is an influential early example of a fiber bundle. Technically, Hopf found a many-to-one continuous function (or "map") from the 3-sphere onto the 2-sphere such that each distinct point of the 2-sphere comes from a distinct circle of the 3-sphere (Hopf 1931). Thus the 3-sphere is composed of fibers, where each fiber is a circle — one for each point of the 2-sphere.

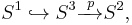

This fiber bundle structure is denoted

where S3 (the 3-sphere) is the total space, S2 (the ordinary 2-sphere) the base space, S1 (a circle) the fiber space, and p: S3→S2 (Hopf's map) the bundle projection. The Hopf fibration, like any fiber bundle, has the important property that it is locally a product space. However it is not a trivial fiber bundle, i.e., S3 is not (globally) a product of S2 and S1. This has many implications: for example the existence of this bundle shows that the higher homotopy groups of spheres are not trivial in general. It also provides a basic example of a principal bundle, by identifying the fiber with the circle group.

Stereographic projection of the Hopf fibration induces a remarkable structure on R3, in which space is filled with nested tori made of linking Villarceau circles. Here each fiber projects to a circle in space (one of which is a "circle through infinity" — a line). Each torus is the stereographic projection of the inverse image of a circle of latitude of the 2-sphere. (Topologically, a torus is the product of two circles.) One of these tori is illustrated by the image of linking keyrings on the right.

There are numerous generalizations of the Hopf fibration. The unit sphere in Cn+1 fibers naturally over CPn with circles as fibers, and there are also real, quaternionic, and octonionic versions of these fibrations. In particular, the Hopf fibration belongs to a family of four fiber bundles in which the total space, base space, and fiber space are all spheres:

In fact these are the only such fibrations between spheres, which fact is related to Hurwitz's Theorem.

The Hopf fibration is important in twistor theory.

Contents |

Definition and construction

For any natural number n, an n-dimensional sphere, or n-sphere, can be defined as the set of points in an (n+1)-dimensional space which are a fixed distance from a central point. For concreteness, the central point can be taken to be the origin, and the distance of the points on the sphere from this origin can be assumed to be a unit length. With this convention, the n-sphere, Sn, consists of the points (x1, x2, …, xn+1) in Rn+1 with x12 + x22 + ⋯+ xn+12 = 1. For example, the 3-sphere consists of the points (x1, x2, x3, x4) in R4 with x12 + x22 + x32 + x42 = 1.

The Hopf fibration p: S3 → S2 of the 3-sphere over the 2-sphere can be defined in several ways.

Direct construction

Identify R4 with C2 and R3 with C×R (where C denotes the complex numbers) by writing:

- (x1, x2, x3, x4) as (z0 = x1 + ix2, z1 = x3 + ix4); and

- (x1, x2, x3) as (z = x1 + ix2, x = x3).

Thus S3 is identified with the subset of all (z0, z1) in C2 such that |z0|2 + |z1|2 = 1, and S2 is identified with the subset of all (z, x) in C×R such that |z|2 + x2 = 1. (Here, for a complex number z = x + iy, |z|2 = z z∗ = x2 + y2, where the star denotes the complex conjugate.) Then the Hopf fibration p is defined by

- p(z0, z1) = (2z0z1∗, |z0|2 − |z1|2).

The first component is a complex number, whereas the second component is real. Any point on the 3-sphere must have the property that |z0|2 + |z1|2 = 1. If that is so, then p(z0, z1) lies on the unit 2-sphere in C×R, as may be shown by squaring the complex and real components of p

Furthermore, if two points on the 3-sphere map to the same point on the 2-sphere, i.e., if p(z0, z1) = p(w0, w1), then (w0, w1) must equal (λ z0, λ z1) for some complex number λ with |λ|2 = 1. The converse is also true; any two points on the 3-sphere that differ by a common complex factor λ map to the same point on the 2-sphere. These conclusions follow, because the complex factor λ cancels with its complex conjugate λ∗ in both parts of p: in the complex 2z0z1∗ component and in the real component |z0|2 − |z1|2.

Since the set of complex numbers λ with |λ|2 = 1 form the unit circle in the complex plane, it follows that for each point m in S2, the inverse image p−1(m) is a circle, i.e., p−1m ≅ S1. Thus the 3-sphere is realized as a disjoint union of these circular fibers.

Geometric interpretation using the complex projective line

A geometric interpretation of the fibration may be obtained using the complex projective line, CP1, which is defined to be the set of all complex one dimensional subspaces of C2. Equivalently, CP1 is the quotient of C2\{0} by the equivalence relation which identifies (z0, z1) with (λ z0, λ z1) for any nonzero complex number λ. On any complex line in C2 there is a circle of unit norm, and so the restriction of the quotient map to the points of unit norm is a fibration of S3 over CP1.

CP1 is diffeomorphic to a 2-sphere: indeed it can be identified with the Riemann sphere C∞ = C ∪ {∞}, which is the one point compactification of C (obtained by adding a point at infinity). The formula given for p above defines an explicit diffeomorphism between the complex projective line and the ordinary 2-sphere in 3-dimensional space. Alternatively, the point (z0, z1) can be mapped to the ratio z1/z0 in the Riemann sphere C∞.

Fiber bundle structure

The Hopf fibration defines a fiber bundle, with bundle projection p. This means that it has a "local product structure", in the sense that every point of the 2-sphere has some neighborhood U whose inverse image in the 3-sphere can be identified with the product of U and a circle: p−1(U) ≅ U×S1. Such a fibration is said to be locally trivial.

For the Hopf fibration, it is enough to remove a single point m from S2 and the corresponding circle p−1(m) from S3; thus one can take U = S2\{m}, and any point in S2 has a neighborhood of this form.

Geometric interpretation using rotations

Another geometric interpretation of the Hopf fibration can be obtained by considering rotations of the 2-sphere in ordinary 3-dimensional space. The rotation group SO(3) has a double cover, the spin group Spin(3), diffeomorphic to the 3-sphere. The spin group acts transitively on S2 by rotations. The stabilizer of a point is isomorphic to the circle group. It follows easily that the 3-sphere is a principal circle bundle over the 2-sphere, and this is the Hopf fibration.

To make this more explicit, there are two approaches: the group Spin(3) can either be identified with the group Sp(1) of unit quaternions, or with the special unitary group SU(2).

In the first approach, a vector (x1, x2, x3, x4) in R4 is interpreted as a quaternion q ∈ H by writing

The 3-sphere is then identified with the quaternions of unit norm, i.e., those q ∈ H for which |q|2 = 1, where |q|2 = q q∗, which is equal to x12 + x22 + x32 + x42 for q as above.

On the other hand, a vector (y1, y2, y3) in R3 can be interpreted as an imaginary quaternion

Then, as is well-known since Cayley (1845), the mapping

is a rotation in R3: indeed it is clearly an isometry, since |q p q∗|2 = q p q∗ q p∗ q∗ = q p p∗ q∗ = |p|2, and it is not hard to check that it preserves orientation.

In fact, this identifies the group of unit quaternions with the group of rotations of R3, modulo the fact that the unit quaternions q and −q determine the same rotation. As noted above, the rotations act transitively on S2, and the set of unit quaternions q which fix a given unit imaginary quaternion p have the form q = u + v p, where u and v are real numbers with u2 + v2 = 1. This is a circle subgroup. For concreteness, one can take p = k, and then the Hopf fibration can be defined as the map sending a unit quaternion q to q k q∗.

This approach is related to the direct construction by identifying a quaternion q = x1 + i x2 + j x3 + k x4 with the 2×2 matrix:

This identifies the group of unit quaternions with SU(2), and the imaginary quaternions with the skew-hermitian 2×2 matrices (isomorphic to C×R).

Explicit formulae

The rotation induced by a unit quaternion q = w + i x + j y + k z is given explicitly by the orthogonal matrix

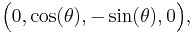

Here we find an explicit real formula for the bundle projection. For, the fixed unit vector along the z axis, (0,0,1), rotates to another unit vector,

which is a continuous function of (w,x,y,z). That is, the image of q is where it aims the z axis. The fiber for a given point on S2 consists of all those unit quaternions that aim there.

To write an explicit formula for the fiber over a point (a,b,c) in S2, we may proceed as follows. Multiplication of unit quaternions produces composition of rotations, and

is a rotation by 2θ around the z axis. As θ varies, this sweeps out a great circle of S3, our prototypical fiber. So long as the base point, (a,b,c), is not the antipode, (0,0,−1), the quaternion

will aim there. Thus the fiber of (a,b,c) is given by quaternions of the form q(a,b,c)qθ, which are the S3 points

Since multiplication by q(a,b,c) acts as a rotation of quaternion space, the fiber is not merely a topological circle, it is a geometric circle. The final fiber, for (0,0,−1), can be given by using q(0,0,−1) = i, producing

which completes the bundle.

Thus, a simple way of visualizing the Hopf fibration is as follows. Any point on the 3-sphere is equivalent to a quaternion, which in turn is equivalent to a particular rotation of a Cartesian coordinate frame in three dimensions. The set of all possible quaternions produces the set of all possible rotations, which moves the tip of one unit vector of such a coordinate frame (say, the z vector) to all possible points on a unit 2-sphere. However, fixing the tip of the z vector does not specify the rotation fully; a further rotation is possible about the z-axis. Thus, the 3-sphere is mapped onto the 2-sphere, plus a single rotation.

Fluid Mechanics

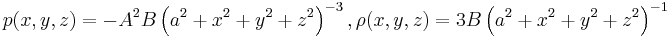

If the Hopf fibration is treated as a vector field in 3 dimensional space then there is a solution to the (compressible, non-viscous) Navier-Stokes equations of fluid dynamics in which the fluid flows along the circles of the projection of the Hopf fibration in 3 dimensional space. The size of the velocities, the density and the pressure can be chosen at each point to satisfy the equations. All these quantities fall to zero going away from the centre. If a is the distance to the inner ring, the velocities, pressure and density fields are given by:

for arbitrary constants A and B. Similar patterns of fields are found as soliton solutions of magnetohydrodynamics[1]:

Generalizations

The Hopf construction, viewed as a fiber bundle p: S3 → CP1, admits several generalizations, which are also often known as Hopf fibrations. First, one can replace the projective line by an n-dimensional projective space. Second, one can replace the complex numbers by any (real) division algebra, including (for n = 1) the octonions.

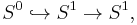

Real Hopf fibrations

A real version of the Hopf fibration is obtained by regarding S1 as a subset of R2 in the usual way and factoring out by unit real multiplication to obtain and a fiber bundle S1 → RP1 over the real projective line with fiber S0 = {1, -1}. Just as CP1 is diffeomorphic to a sphere, RP1 is diffeomorphic to a circle.

More generally, the n-sphere Sn fibers over real projective space RPn with fiber S0.

Complex Hopf fibrations

The Hopf construction gives circle bundles p : S2n+1 → CPn over complex projective space. This is actually the restriction of the tautological line bundle over CPn to the unit sphere in Cn+1.

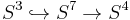

Quaternionic Hopf fibrations

Similarly, one can regard S4n−1 as lying in Hn (quaternionic n-space) and factor out by unit quaternion (= S3) multiplication to get HPn. In particular, since S4 = HP1, there is a bundle S7 → S4 with fiber S3.

Octonionic Hopf fibrations

A similar construction with the octonions yields a bundle S15 → S8 with fiber S7. One can regard S8 as the octonionic projective line OP1.

Although one can also define an octonionic projective plane, OP2, S31 does not fiber over it.

Fibrations between spheres

Sometimes the term "Hopf fibration" is restricted to the fibrations between spheres obtained above, which are

- S1 → S1 with fiber S0

- S3 → S2 with fiber S1

- S7 → S4 with fiber S3

- S15 → S8 with fiber S7

As a consequence of Adams' theorem, these are the only fiber bundles with spheres as total space, base space, and fiber.

Geometry and applications

The Hopf fibration has many implications, some purely attractive, others deeper. For example, stereographic projection of S3 to R3 induces a remarkable structure in R3, which in turn illuminates the topology of the bundle (Lyons 2003). Stereographic projection preserves circles and maps the Hopf fibers to geometrically perfect circles in R3 which fill space. Here there is one exception: the Hopf circle containing the projection point maps to a straight line in R3 — a "circle through infinity".

The fibers over a circle of latitude on S2 form a torus in S3 (topologically, a torus is the product of two circles) and these project to nested toruses in R3 which also fill space. The individual fibers map to linking Villarceau circles on these tori, with the exception of the circle through the projection point and the one through its opposite point: the former maps to a straight line, the latter to a unit circle perpendicular to, and centered on, this line, which may be viewed as a degenerate torus whose radius has shrunken to zero. Every other fiber image encircles the line as well, and so, by symmetry, each circle is linked through every circle, both in R3 and in S3. Two such linking circles form a Hopf link in R3

Hopf proved that the Hopf map has Hopf invariant 1, and therefore is not null-homotopic. In fact it generates the homotopy group π3(S2) and has infinite order.

In quantum mechanics, the Riemann sphere is known as the Bloch sphere, and the Hopf fibration describes the topological structure of a quantum mechanical two-level system or qubit. Similarly, the topology of a pair of entangled two-level systems is given by the Hopf fibration

.

.

Discrete examples

The regular 4-polytopes: 8-cell (Tesseract), 24-cell, and 120-cell, can each be partitioned into disjoint great circle rings of cells forming discrete Hopf fibrations of these polytopes. The Tesseract partitions into two interlocking rings of four cubes each. The 24-cell partitions into four rings of six octahedrons each. The 120-cell partitions into twelve rings of ten dodecahedrons each.

References

- ^ Kamchatno, A. M (1982), Topological solitons in magnetohydrodynamics, http://www.jetp.ac.ru/cgi-bin/dn/e_055_01_0069.pdf

- Cayley, Arthur (1845), "On certain results relating to quaternions", Philosophical Magazine 26: 141–145, http://www.archive.org/details/collmathpapers01caylrich; reprinted as article 20 in Cayley, Arthur (1889), The collected mathematical papers of Arthur Cayley, I, (1841–1853), Cambridge University Press, pp. 123–126, http://www.hti.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/pageviewer-idx?c=umhistmath;cc=umhistmath;rgn=full%20text;idno=ABS3153.0001.001;didno=ABS3153.0001.001;view=image;seq=00000140

- Hopf, Heinz (1931), "Über die Abbildungen der dreidimensionalen Sphäre auf die Kugelfläche", Mathematische Annalen (Berlin: Springer) 104 (1): 637–665, doi:10.1007/BF01457962, ISSN 0025-5831, http://www.digizeitschriften.de/index.php?id=loader&tx_jkDigiTools_pi1%5BIDDOC%5D=363429&L=2

- Hopf, Heinz (1935), "Über die Abbildungen von Sphären auf Sphären niedrigerer Dimension", Fundamenta Mathematicae (Warsaw: Polish Acad. Sci.) 25: 427–440, ISSN 0016-2736

- Lyons, David W. (April 2003), "An Elementary Introduction to the Hopf Fibration" (PDF), Mathematics Magazine 76 (2): 87–98, doi:10.2307/3219300, ISSN 0025-570X, JSTOR 3219300, http://csunix1.lvc.edu/~lyons/pubs/hopf_paper_preprint.pdf

- Mosseri, R.; Dandoloff, R. (2001), "Geometry of entangled states, Bloch spheres and Hopf fibrations", J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 34 (47): 10243–10252, arXiv:quant-ph/0108137, doi:10.1088/0305-4470/34/47/324.

- Steenrod, Norman (1951), The Topology of Fibre Bundles, PMS 14, Princeton University Press (published 1999), ISBN 978-0-691-00548-5, http://books.google.com/?id=m_wrjoweDTgC&printsec=frontcover&dq=%22The+Topology+of+Fibre+Bundles%22

- Urbantke, H.K. (2003), "The Hopf fibration-seven times in physics", Journal of Geometry and Physics 46 (2): 125–150, doi:10.1016/S0393-0440(02)00121-3.

External links

- Dimensions Math Chapters 7 and 8 illustrate the Hopf fibration with animated computer graphics.

- YouTube animation of the construction of the 120-cell By Gian Marco Todesco shows the Hopf fibration of the 120-cell.